The concept of open space is particularly fashionable just now. For some, it is an exciting vision of a digitised work environment. For others, it sounds more like a dangerous threat, equal to that of open-plan offices and desk sharing. So how much openness does a contemporary office need? A critical analysis between errors and misdirection.

In order to come close to possible answers, we must first ask the question of where and how office workers actually work today. Not that they can be lumped together as one – a field sales employee has a completely different daily routine from a bookkeeper – but it is a fact that permanent workplaces on average are only used one third of the time during the course of a working week. We spend the other two thirds away from our (own) desk in meetings, breaks, co-working areas, working from home or travelling. We could even continue the list. Experts have coined the term “activity-based working”: We use the working locations which are best suited to our current activity.

Cubicles or open plan: Which office design is better?

“Now, this is definitely the wrong question,” says Bernhard Kern, Managing Director of Roomware Consulting – a company which deals with office development and design. “The right office design is determined by the respective organisation and must suit the company culture. The decision about office design always goes together with the future ways of working.”

Open-plan offices are very popular among many companies because, unsurprisingly, they are cheaper. A rule of thumb states that the area costs are around one third lower than for office buildings with classic cubicle structures. However, there are a lot of negative facets to this economic aspect in any case. Relabelling open plan as open space also doesn’t help. The problems with open space are known and are difficult to get under control. Noise irritation, disruptions to concentration and – something which may sound paradoxical as it’s currently sold as a great advantage – the impairment of communication: In a current Harvard study, it was established that personal conversations in open spaces, meaning open-plan offices, have reduced by up to 70 percent compared with small-structured offices. At the same time, digital communication via Messenger or email increased by 67 percent. The result: Employees are hiding behind their computers, huddling under their headphones and silently completing their work.

So, does this mean that we are moving back towards the traditional cubicle office? With a large desk and opulent linear metres of storage space? Hardly, even if the cubicles are, as before, the most popular office design among employees. According to the Fraunhofer institute, just under 50 percent of people still work in classic offices with cubicle structures. Apart from that, each change is initially viewed with a sceptical eye. As before, the cubicle office is the manifestation of hierarchy, status and the claim of ownership for many employees.

Yet even in the classic cell office, the negative aspects are also serious: In many company areas, the rigid cubicle structure prevents modern, collaboration-oriented working processes. There are also high structural costs and poor spatial efficiency to consider – and this, as stated above, with an actual workplace presence of barely more than 30 to 50 percent.

One-person cubicles completely support concentrated working; with two-person or four-person cubicles, the situation is completely different: Here, communication and the associated noise is perceived as even more disruptive than the base level of noise in open room structures.

The paradox in the discussion “open plan versus cubicles” is that the presumed strengths of the respective office design are perceived in completely the opposite way in reality.

Open units bring communication and concentration into balance.

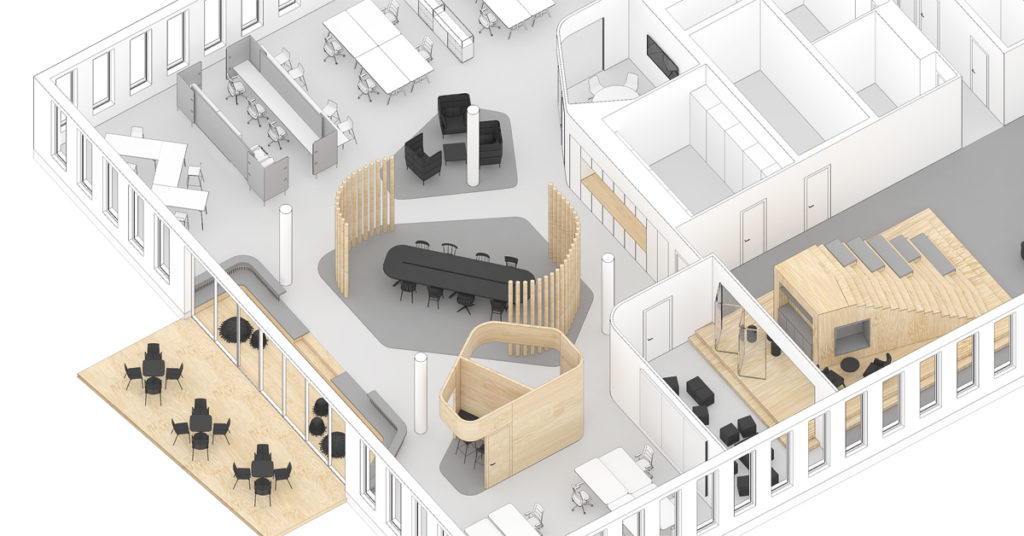

In his book, “2025 – So arbeiten wir in der Zukunft” [This is how we work in the future], futurologist Sven Gabor Janszky assumes that in the future, there will be three essential room scenarios in office buildings: silent rooms for highly concentrated work, highly technological communication rooms for real and virtual meetings as well as co-working spaces which offer an ideal environment for collaboration. While the first two of these room scenarios are designed as classic cubicle solutions, co-working areas leave a great deal of leeway for organisation and design in the spatial implementation. Here, one thing can be observed most of the time: They are neither open plan nor cubicles. Experts, such as Prague architect Martin Stara, whose architecture office Studio Perspektiv specialises in new-work office designs, are talking about open units here. These are rescaled, small-structured yet open room areas which above all focus on collaboration: project rooms, libraries, work cafes, communication islands, retreat niches, team offices, lobbies, gardens, living rooms, etc.; the design implementation possibilities are incredibly diverse. Open units are the answer to activity-based working. They create the freedom to select the ideal working location for your activity. Here, the personalised desk only has a subordinate role. Storage space is even less important because notebooks and the cloud take on this function.

Open units are an integrative component of an open room design, but structured into smaller, spatial units, divided and, depending on their purpose, more or less screened off, visually and acoustically. The unit concept, as we know from organisation theory, is also implemented spatially. The main advantage of these organisational units is the support offered to collaboration. In creative innovation processes, the units promote the openness of thought on one hand and on the other, the necessary seclusion to permit concentrated teamwork and project work.

The costs argument still remains and the question of how to create the financial wiggle room for the additional open units. With the broad forgoing of expensive, space-intensive cubicle offices with the same rescaling of classic workplaces – whether it be through desk-sharing or savings from storage areas which are no longer required – it should easily be enough.